FÆLLES UDTALELSE OM DE FORRINGEDE VILKÅR FOR YTRINGS- OG MEDIEFRIHED I TYRKIET

Til forelæggelse for FN’s FN Menneskerettighedsråd 34. Samling, punkt 4: Menneskerettigheds-situationer, der kræver Rådets opmærksomhed

Til forelæggelse for FN’s FN Menneskerettighedsråd 34. Samling, punkt 4: Menneskerettigheds-situationer, der kræver Rådets opmærksomhed

Fremført af Sarah Clarke, International PEN

Den 15. marts 2017

Hr. formand

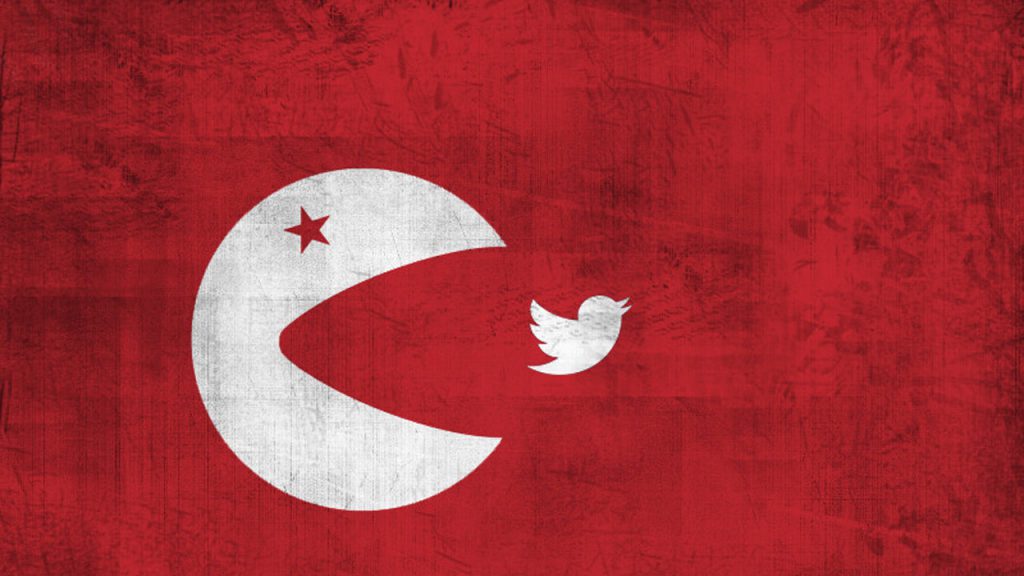

International PEN, ARTICLE 19 og 67 andre organisationer skal herved udtrykke vores dybe bekymring over den eskalerende forværring af ytrings- og mediefriheden, som Tyrkiet har set siden det voldelige og fordømmelige kupforsøg i juli 2016.

Over 180 nyhedsmedier er lukket ned ved præsidentielt dekret efter indførelse af undtagelsestilstand. Mindst 148 forfattere, journalister og mediefolk er fængslet, deriblandt Ahmet Şık, Kadri Gürsel, Ahmet og Mehmet Altan, Ayşe Nazli Ilıcak og İnan Kizilkaya, hvilket nu gør Tyrkiet til det land i verden, der har sat flest journalister i fængsel. De tyrkiske myndigheder misbruger undtagelsestilstanden til en alt for vidtgående begrænsning af grundlæggende rettigheder og friheder, der kvæler kritiske røster og begrænser mangfoldigheden af de synspunkter og udtalelser, der er tilgængelige i det offentlige rum.

Disse begrænsninger har nået nye højder forud for den afgørende folkeafstemning 16. april om forfatningsmæssige reformer, som drastisk vil udvide den udøvende magts beføjelser. De tyrkiske myndigheders kampagne har været skæmmet af trusler, arrestationer og retsforfølgelse af dem, der har givet udtryk for kritik af de foreslåede ændringer. Flere medlemmer af oppositionen er blevet anholdt på terroranklager. Tusindvis af offentligt ansatte, herunder hundredvis af akademikere og modstandere af de forfatningsmæssige reformer, blev afskediget i februar. Markante ’Nej’-demonstranter er blevet tilbageholdt, hvilket har forværret det samlede klima af mistro og frygt. Rettighederne til at nyde godt af ytrings- og informationsfrihed, som er så afgørende for retfærdige og frie valg, er i fare.

I tiden op til folkeafstemningen er behovet for mediepluralisme er vigtigere end nogensinde. Vælgerne har ret til at blive behørigt informeret og kunne gøre sig bekendt med alle oplysninger og synspunkter, herunder afvigende røster, i tilstrækkelig god tid. Den fremherskende atmosfære bør være præget af respekt for menneskerettighederne og de grundlæggende frihedsrettigheder uden frygt for repressalier.

Vi skal derfor opfordre dette råd, dets medlemmer og observatører til at opfordre de tyrkiske myndigheder til:

- At garantere lige sendetid for alle parter og give mulighed for at formidle alle oplysninger i videst muligt omfang for at sikre, at vælgerne er fuldt informeret;

- At sætte en stopper for klimaet af mistro og frygt ved: 1) Straks at løslade alle dem, der holdes i fængsel for at udøve deres ret til menings- og ytringsfrihed; 2) At ophøre med at retsforfølge og tilbageholde journalister, der holdes interneret alene på grundlag af indholdet af deres journalistisk eller påståede partitilhørsforhold; 3) At indstille den udøvende magts indblanding i redaktionelle beslutninger, afskedigelser af journalister og redaktører – og pres imod og intimidering af kritiske nyhedsmedier og journalister

- At tilbagekalde undtagelsestilstandens alt for vidtgående bestemmelser, hvis håndhævelse i praksis er uforenelige med Tyrkiets menneskeretsforpligtelser.

Tak hr. Formand

Underskrevet af 31 PEN-centre, deriblandt Dansk PEN, foruden organisationer som ARTICLE 19, Journalister Uden Grænser, Mediawatch og mange andre. Også netværket Fri Debat tilslutter sig opfordringen.

ActiveWatch – Media Monitoring Agency

Adil Soz – International Foundation for Protection of Freedom of Speech

Albanian Media Institute

Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain

ARTICLE 19

Association of European Journalists

Basque PEN

Brazilian Association for Investigative Journalism

Canadian Journalists for Free Expression

Cartoonists Rights Network International

Center for Independent Journalism – Hungary

Croatian PEN centre

Danish PEN

Digital Rights Foundation

English PEN

European Centre for Press and Media Freedom

European Federation of Journalists

Finnish PEN

Foro de Periodismo Argentino

German PEN

Global Editors Network

Gulf Centre for Human Rights

Human Rights Watch

Icelandic PEN

Independent Chinese PEN Center

Independent Journalism Center – Moldova

Index on Censorship

Institute for Media and Society

International Press Institute

International Publishers Association

Journaliste en danger

Media Foundation for West Africa

Media Institute of Southern Africa

Media Watch

MYMEDIA

Nigeria PEN Centre

Norwegian PEN

Pacific Islands News Association

Pakistan Press Foundation

Palestine PEN

PEN American Center

PEN Austria

PEN Canada

PEN Català

PEN Centre in Bosnia and Herzegovina

PEN Centre of German-Speaking Writers Abroad

PEN Eritrea in exile

PEN Esperanto

PEN Estonia

PEN France

PEN International

PEN Melbourne

PEN Myanmar

PEN Romania

PEN Suisse Romand

PEN Trieste

Portuguese PEN Centre

Punto24

Reporters Without Borders

Russian PEN Centre

San Miguel PEN

Serbian PEN Centre

Social Media Exchange – SMEX

South East Europe Media Organisation (SEEMO)

South East European Network for Professionalization of Media

Vigilance pour la Démocratie et l’État Civique

Wales PEN Cymru

World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers (WANIFRA)